The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) is, after much debate and anticipation, finalized. The long journey since April 2021, with its tortuous negotiations and messy compromises, can be confusing even for those of us in Europe, who have been following it closely. I suspect it is even more bewildering if you are sitting in California, Dubai, or Singapore, and lack a large European presence to help make sense of it.

What does the AIA actually say?

The final text has not been shared yet, but the broad outline is clear. The AIA aims to ensure that AI systems operating within the European market respect fundamental rights and EU values. In practice, it places specific obligations on public and private organizations that build or use AI systems, based on the perceived risks associated with specific use cases. For instance, emotion recognition and biometric categorisation to infer sensitive data are completely banned. In contrast, CV-sorting software for recruitment procedures and credit applications are authorized but labeled as high-risk and thus subject to strict obligations before they can be put on the market.

One area that has attracted a lot of attention this year is the AIA’s approach to General Purpose AI (GPAI) and Foundation Models. The latter must comply with specific transparency obligations before they are placed in the market, such as drawing up technical documentation, complying with EU copyright law and providing information about the content used for training. Plus, high-impact GPAI models which pose systemic risk will be subject to additional binding obligations related to performance evaluation, risk management, adversarial testing, and monitoring of incidents. These new obligations will be operationalised through codes of practice developed by a multistakeholder community that includes industry actors, academics, civil society, and EU commission officials.

So is this “GDPR for AI”?

Many commentators have predicted that the EU AIA will have a global impact, similar to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which has set the standard on data privacy.

However, there are some important differences from GDPR: For one thing, the breadth and complexity of the regulatory landscape will be much higher because the AIA complements sectorial regulations, it does not replace them. That’s particularly true for highly regulated industries such as financial services and healthcare. Navigating the interplay between existing regulations and the AIA will be critical to get implementation right.

Also, given the strategic importance of AI, other countries will probably develop their own AI governance standards based on their national economic and geopolitical goals. In the long term, these regulations are likely to converge to facilitate cross-border trade. But in the short term, business executives face the possibility of having to deal with different regulatory expectations depending on the jurisdictions in which they operate.

Further, some companies may be tempted to provide a different version of their AI products and services to the EU for the reason mentioned above. Here, I’m particularly thinking about foundation models. Some market leaders have already indicated that they are reluctant to disclose details of its training methods and data sources.

Can’t you just wait for a few years before acting?

The easy answer would be to wait and watch. After all, there is work to be done to establish the underlying standards, and a two-year grace period is usual with such large scale regulations, anyway. But that would be the wrong response, for three very good reasons:

- There is solid business rationale to build most of the underlying principles into your product and strategy from the outset. Whether you are a provider or user of AI systems, you will want to ensure that they are trustworthy. You will want to prevent harm to your customers or your own reputation. You are much more likely to achieve greater adoption and value at scale if you address these issues from the start, even if you are not immediately impacted by the regulations.

- Social and government pressure on AI safety and quality is not limited to the EU. Many of the same concerns are prominent elsewhere too, as seen in the recent US Executive Order. We expect that other countries and regions will hasten to implement their own guidelines or regulations in the near future, using the EU AIA as a guide, perhaps even setting them into action prior to the time when the EU AIA enters its enforcement period. So building up your “AI quality muscle” using the AIA as a catalyst will help you, no matter where you operate.

- Making your AI systems safe and trustworthy is not like flipping a switch. It requires sustained effort over time to be effective, across people, processes, technology and governance layers. Starting now is a necessity, not a luxury.

So what can you do today, sitting outside of the EU?

In order to minimize your general AI risk or specifically utilize AI in the EU, there are three places to start:

First, rapidly build a working hypothesis of your regulatory exposure. Are you using any AI system that may fall under the unacceptable risk category? What other AI use cases in your portfolio are likely to get tagged as high risk use cases? To what extent will existing regulations – and your mechanisms to adhere to them – cover you already?

Second, establish AI quality and risk management as core operational capabilities. As AI-based applications are increasingly important drivers of business and increasingly exposed to the end customer, AI quality and risk management need to move to the forefront. They are not just a corporate affairs or government relations function, but something that is understood and owned by those sponsoring, building and using AI-enabled systems in your organization.

These capabilities will help you track the evolution of detailed standards in response to the AIA – such as the work at the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN), and the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (CENELEC). It will allow you to update your baseline hypothesis with the inevitable changes and refinements in requirements over time. Most importantly, it will help you ensure that your processes, people and technology are ready for compliance in the coming years.

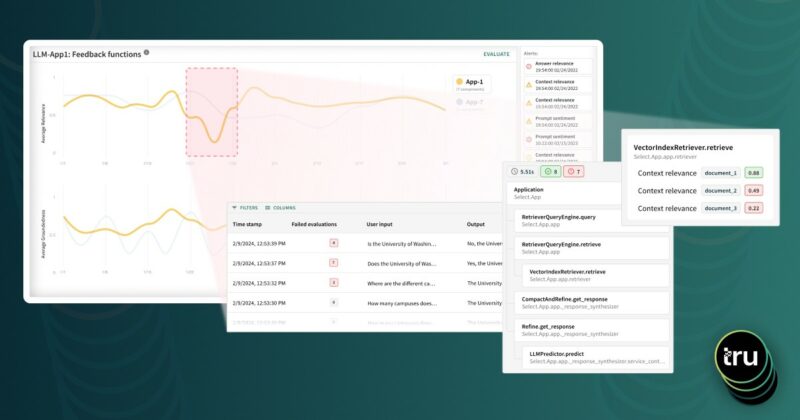

Third, get serious about the missing “AI quality” layer in your tech stack. Ensuring compliance with something as significant as the AIA (and its equivalents elsewhere in the world) will be highly challenging if you attempt to do this through manual effort alone. A systematic approach is needed – one that designs AI quality into the lifecycle of AI systems. Technology solutions to enable data scientists and ML engineers address fairness, safety and transparency concerns have existed for some time. By embedding these as an integral part of your MLOps landscape, you can start testing, debugging, explaining, and monitoring your AI systems today.